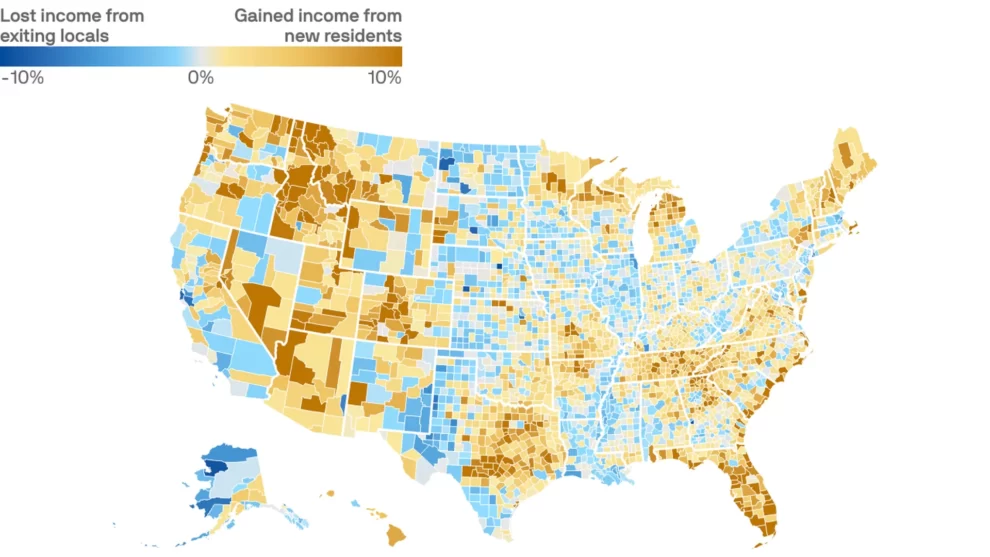

When millions of Americans rethought their living situations during the pandemic, their moves changed the geography of where money is made in the United States.

Why it matters: A new analysis of tax data by the Economic Innovation Group, shared first with Axios, quantifies the reasons some of America’s biggest cities are struggling to rebuild their economies post-pandemic.

- It also shows a surge in income that arrived in many rural and exurban places and in popular vacation destinations.

- Not only did residents leave the biggest cities, but those who left disproportionately had high incomes, meaning the hit to those local economies was larger than migration numbers alone would imply.

By the numbers: In San Francisco, out-migration caused a 20% drop in adjusted gross income from 2020 to 2021 as a share of the taxable income of those who stayed put. In Manhattan, that drop was 13%, and in Boston, 11%.

- These cities were losing high earners. San Francisco out-migrants’ average taxable income was $240,000, while those moving in averaged $134,000. The numbers were similar for Manhattan.

- The biggest percentage rise in income due to migration was in Walton County in the Florida panhandle (+51.6%).

- Other large surges occurred in Collier County, Florida (best-known city: Naples, +31.4%), Pitkin County, Colorado (home of Aspen, +27.4%) and Summit County, Utah (home of Park City, +34.9%).

State of play: In some cities — including Washington, D.C., and New York — income taxes are a major source of municipal revenue. But even places without a county-level income tax depend on residents’ incomes to support the local housing market, retail sales and tax base.

What they’re saying: “The scale of urban income flight is a lot larger than I thought it would be,” said Connor O’Brien, who conducted the analysis at EIG, a Washington-based think tank.

- “It’s very likely that in the last couple of years in superstar cities, high earners have become more mobile while everyone else had been stuck.”

- At the same time, “rural areas caught a break for the first time in a while,” he said.

- There were particularly strong inflows of income in counties near the Canadian border in Michigan, Minnesota and Maine — places that haven’t been magnets for entrepreneurship and investment.

What’s next: The data only covers 2021, so it doesn’t shed light on 2022 and what’s happened so far this year.

- Based on other evidence, O’Brien said, the trend likely eased but does not appear to have reversed.

Source : AXIOS