The true strength of contemporary “Middle Powers” is in their aggregated mass. However, every now and then, one outlier sets fire to the rule book and embarks on its own ambitious response to global affairs, for Australia, Poland is this new upstart.

At first glance you couldn’t get two more distinctly different middle powers than Australia and Poland.

One is a relatively land locked, rising economic, political and military power at the heart of central Europe, seeking to shake off the moniker of a nation as a “speed bump” caught between the might and ambitions of other competing great powers.

The other, an isolated, island continent endowed with an unrivalled resource wealth and overwhelmingly dependent on the benevolence of the global and regional order for its own economic stability and strategic security.

Against this backdrop, we have the ever-mounting strain placed upon the post-Second World War order, that has been led and guaranteed by the United States.

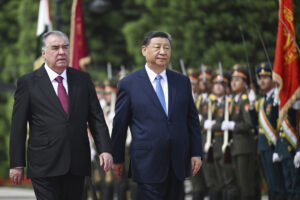

Nowhere is this more evident than in the rapidly deteriorating “situationship” that now colours the dynamic between the United States as the world’s incumbent, pre-eminent global power and the rising superpower, the People’s Republic of China, which are tentatively circling one another, jabbing into the air like heavyweight boxers sizing up their adversary before committing.

This environment of uncertainty is only further compounded by increasing competition from emerging multilateral organisations like the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and BRICS, made up of competing member states including Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, and a growing number of emerging “partners” or “adjacent” states all of which are now realigning their domestic and foreign policies to hasten the collapse of the post-Second World War order.

For nations like Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Western Europe, the post-Second World War order embodied by the United Nations and other multilateral organisations including the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and other organs designed to facilitate an explosion of free trade across the globe paving the way for the modern, interconnected global economy, and period of innovation is coming to an end.

Whether we like it or not and whether we are prepared for it or not, this new paradigm presents new challenges for Australia’s geostrategic policy community and the planning surrounding the Defence Strategic Review (DSR) as for the first time in lived memory, both we, and our great and powerful friend, the United States, face an increasingly contested and competitive world.

However, for many nations, particularly those on the fringes of global centres of power in Europe and Asia, the “new” reality of global economic, political, and strategic great power competition is part of their everyday life and have accordingly shaped their defence and broader strategic policies to maintain their sovereignty and protect their national interests against significantly larger and more powerful great powers.

For Jakub Knopp of the Institute of New Europe, front and centre of this is Poland, a nation which spent much of the 20th century under the occupation of one barbaric regime after another until finally reclaiming its independence following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Strange bedfellows

Knopp highlights the impact the deteriorating geostrategic, economic, and political circumstances are having on established and emerging middle powers like Australia and Poland, respectively, notably following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and mounting Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific.

“The Russian invasion of Ukraine continues to impact global security, challenging standard principles of defence planning and national strategy. Middle powers, whether they be close to the aggression, like Poland, or far from it, like Australia, have been reminded of the looming threat of increasingly assertive autocracies. As dictators proclaim that ‘the world is undergoing profound changes unseen in a century’, both democracies find themselves needing a plan,” Knopp states.

However, despite the seemingly protective insulation of Australia’s geographic isolation (which is now being rapidly replaced by a predicament of proximity), Knopp is clear in articulating the uncomfortable reality which now confronts both Poland and Australia as it relates to the broader decline of the global balance of power.

Knopp states, “Both face a rude awakening. Russia’s invasion exposed capability gaps and inefficient procurement within NATO and throughout the US alliance system. The war has led to foreboding warnings of autocratic aggression, like Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s comments that East Asia could be “another Ukraine” if the region’s democracies fail to prepare. Australia, which has long aligned its foreign policy with the US, cemented that approach through the AUKUS agreement and its new defence strategic review.”

Yet despite this, Australia’s policymakers and the public (largely through apathy and being left out of the debate) have been slow to actually respond to the challenges – yes, further delays to delivering even a modicum of the Albanese government’s vaunted Defence Strategic Review raise serious questions.

Ultimately, Australia is significantly more vulnerable to the changes reshaping the modern geopolitical, economic, and strategic paradigms at home and abroad than Poland is, in particular, our insistence on remaining “part of” Oceania as our main economic, political, and strategic measuring stick allows Australia’s policymakers and the Australian public to live in a state of arrested development when compared to the reality of us being geographically closer and more interconnected with Southeast Asia than the South Pacific.

This arrested development-centric approach contrasts with Poland’s approach to the declining stability of the global and regional balance of power, with Knopp highlighting the stark differences between the two middle powers, particularly as it relates to the broader US participation and commitment to the global order, stating: “Warsaw and Canberra share this history of collaboration with the US. Their loyalty has been proven over the years, in arms procurement and in Afghanistan and Iraq. But such close reliance on US military power has bred complacency. Now, as both countries manage unprecedented change, they find themselves restricted by American strategy. While Poland tries to acquire a leading voice in the NATO alliance by splurging over 4 per cent of its GDP on arms, Australia is further entrenching itself with the US in the Indo-Pacific, confident of American commitment to the region.”

We need to get our skates on

Australia has a rather nasty history and habit of waiting until the absolute last moment before responding to any threat or challenges, seemingly preferring to live in a state of ignorant bliss.

We have to look no further than Australia’s preparation, or lack thereof in the decade leading up to the outbreak of the Second World War and the subsequently precarious position in which the nation found itself as it confronted a rampaging Imperial Japan almost entirely on its own for the first two years of the conflict.

Yet another example is the way in which the Australian public rightfully were horrified by the lack of industrial capacity that COVID-19 revealed, yet now we have returned to a lazy status quo. It appears we are indeed very, very slow learners.

In contrast, Poland is seeking to avoid once again becoming a “speed bump”, caught between competing great powers, and is responding to with haste, something Knopp highlights, stating, “Poland similarly relies on American weaponry, largely ignoring European options. That said, by opting for more equipment from South Korea, including K2 tanks, Chunmoo rocket-artillery systems and FA-50 fighters, Warsaw has refrained from putting every last egg in one basket.

“Whereas Poland’s plans are set to deliver results in five to 10 years, Australia’s nuclear submarines should arrive in the early 2040s. The costs and time requirements of the first pillar of AUKUS render Australian strategy predictable and fairly inflexible, which is especially worrying as it moves into a ‘decisive decade’,” Knopp articulates.

As the old saying goes, you go to war with the military you have, not the one you want, yet Australia seems to be dragging its feet.

Final thoughts

With a new understanding, is it reasonable for Australia to position itself as a “middle” or “regional” power in this rapidly evolving geopolitical environment? Equally, if we are going to brand ourselves as such, shouldn’t we aim for the top tier to ensure we get the best deal for ourselves and our future generations?

Importantly, in this era of renewed competition between autarchy and democracy, this is a conversation that needs to be had in the open with the Australian people, as ultimately, they will be called upon to help implement it, to consent to the direction, and to defend it should diplomacy fail.

This requires a greater degree of transparency and a culture of collaboration between the nation’s strategic policymakers and elected officials and the constituents they represent and serve – equally, this approach will need to entice the Australian public to once again invest in and believe in the future direction of the nation.

Equally, it is important for us to recognise that while we don’t face these challenges in isolation, each and every nation is and will put its own interests first, the COVID-19 pandemic proved that, therefore we can no longer afford to be blindly altruistic in our approach to the nation’s future, to do so is willful ignorance at best and national vandalism at worst.

If we are going to emerge as a prosperous, secure, and free nation in the new era of great power competition, it is clear we will need break the shackles of short-termism and begin to think far more long term, to the benefit of current and future generations of Australians.

Source : Defence Connect